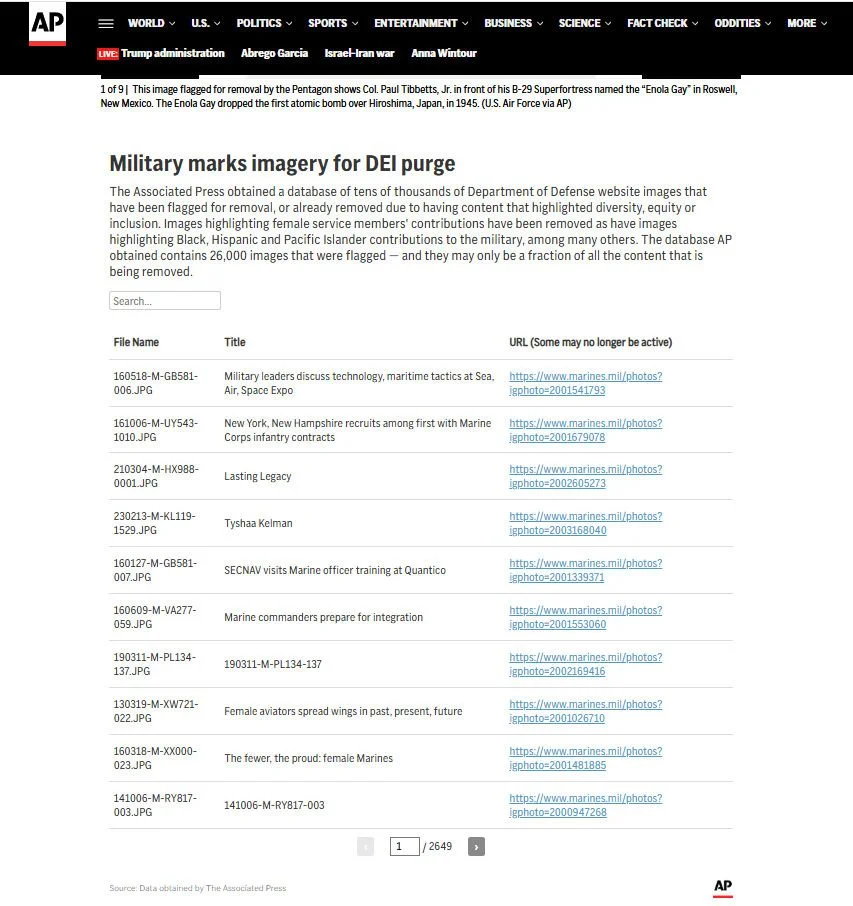

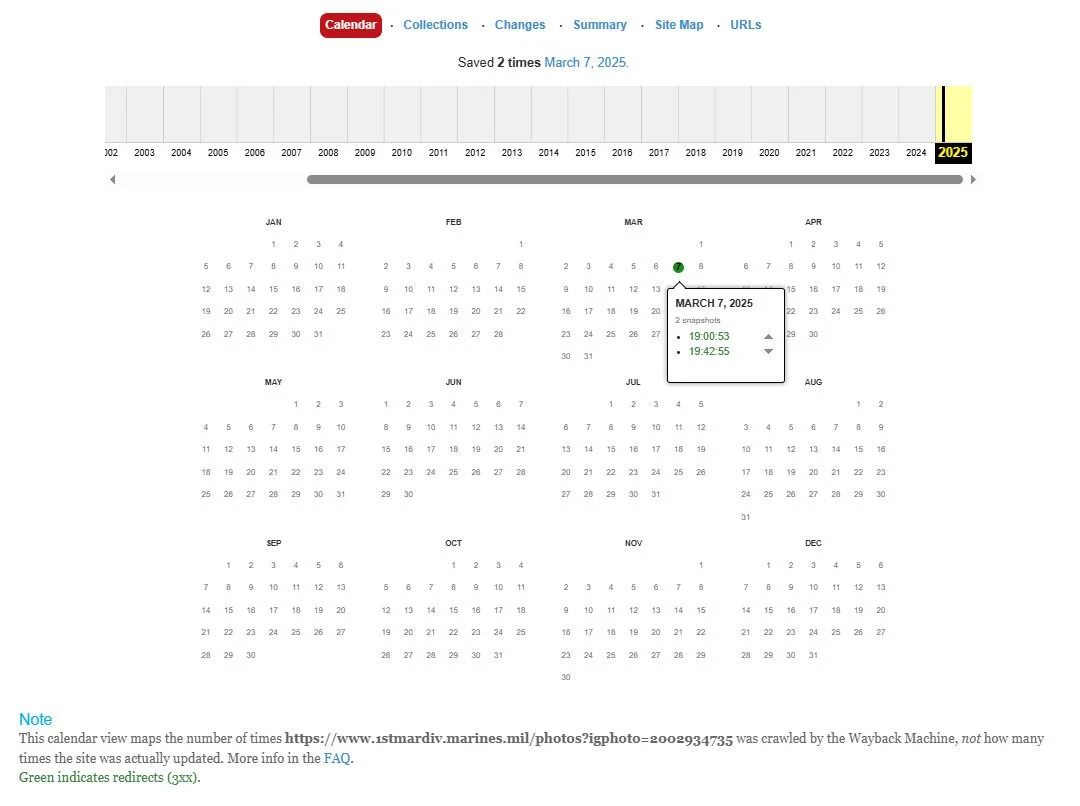

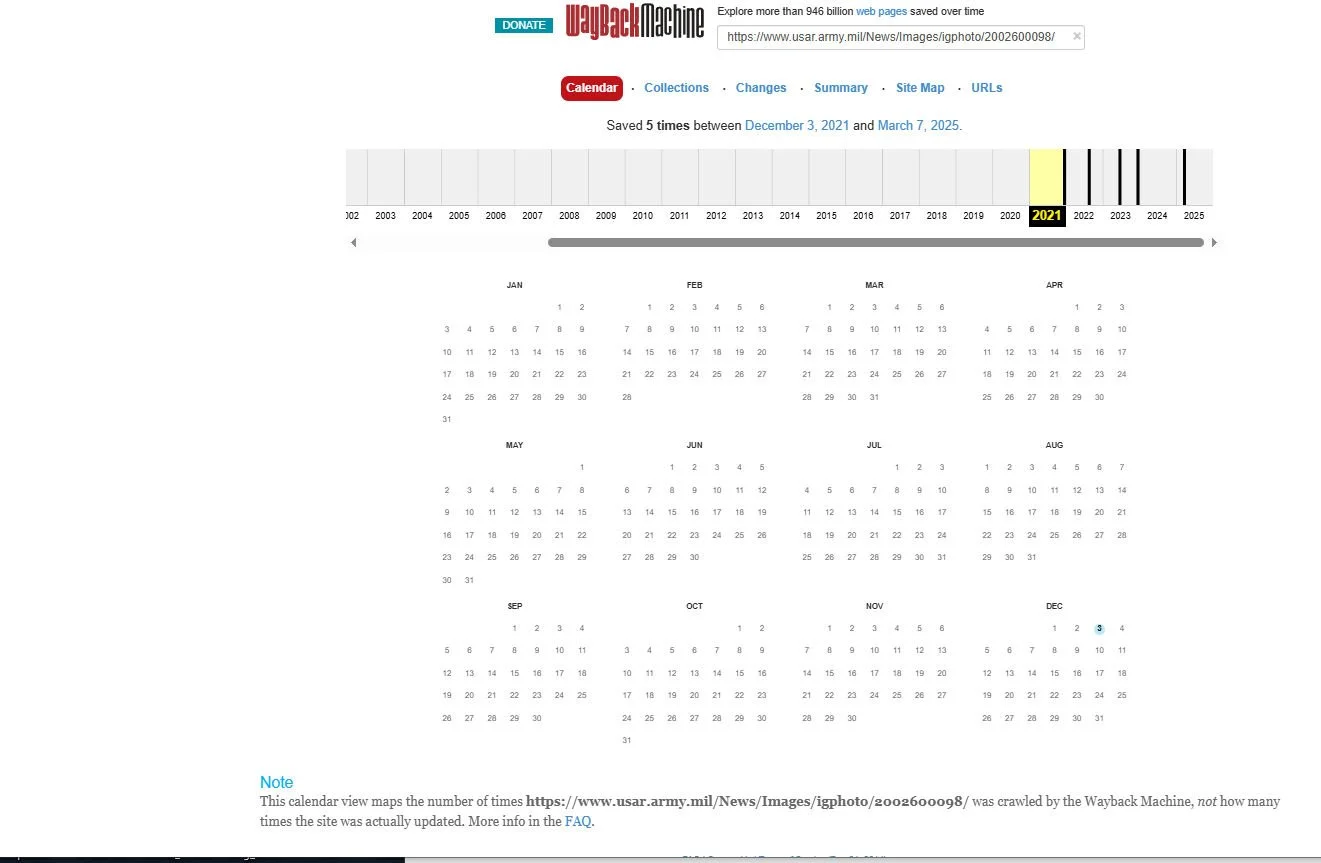

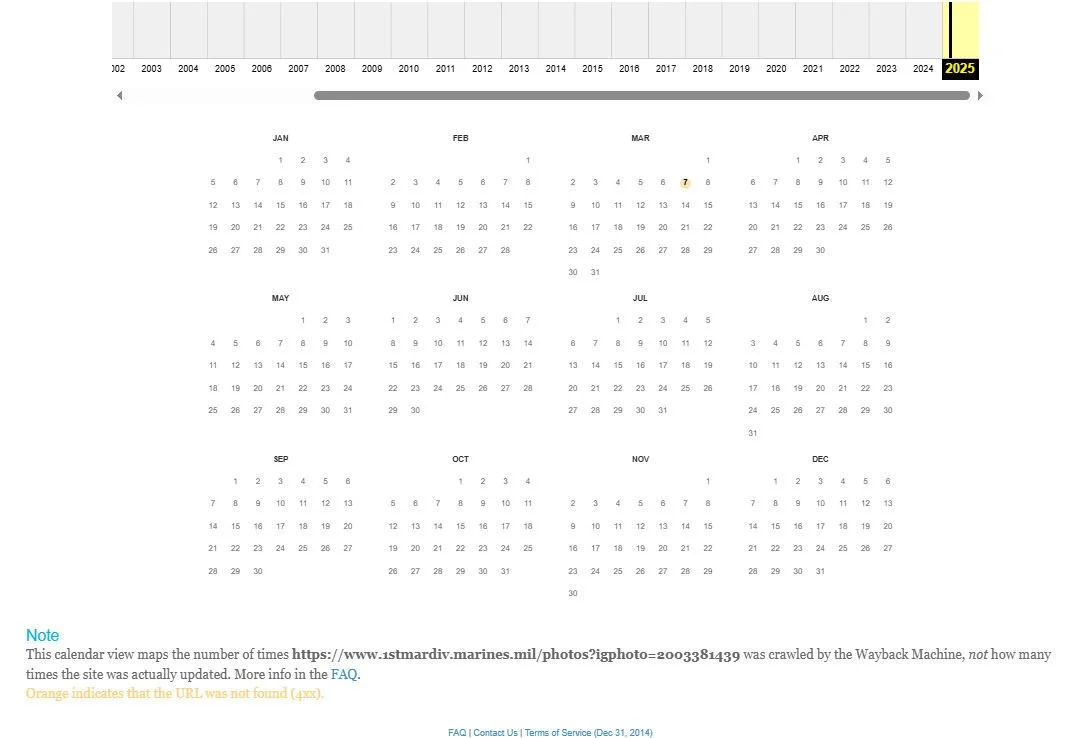

I could visually track the life and disappearance of many of these images. For several URLs, I saw years of blue circles, snapshots taken regularly from 2016 through 2024. Then suddenly nothing in 2025. The digital trail just stopped.

In many cases, I was able to retrieve full pages and images from those archived versions, long after they were removed from the original source. The Wayback Machine helped me recover some content and helped me understand the timeline of erasure.

It was fascinating, and a little haunting, to see pages that had once been viewed regularly go completely dark after 2025.

Other Tools

When URLs failed, I searched by filename in quotes on Google. Tools like TinEye helped me track down reposted images or related files. Each time I found something, it felt like recovering a piece of someone’s legacy.

Making the Painting

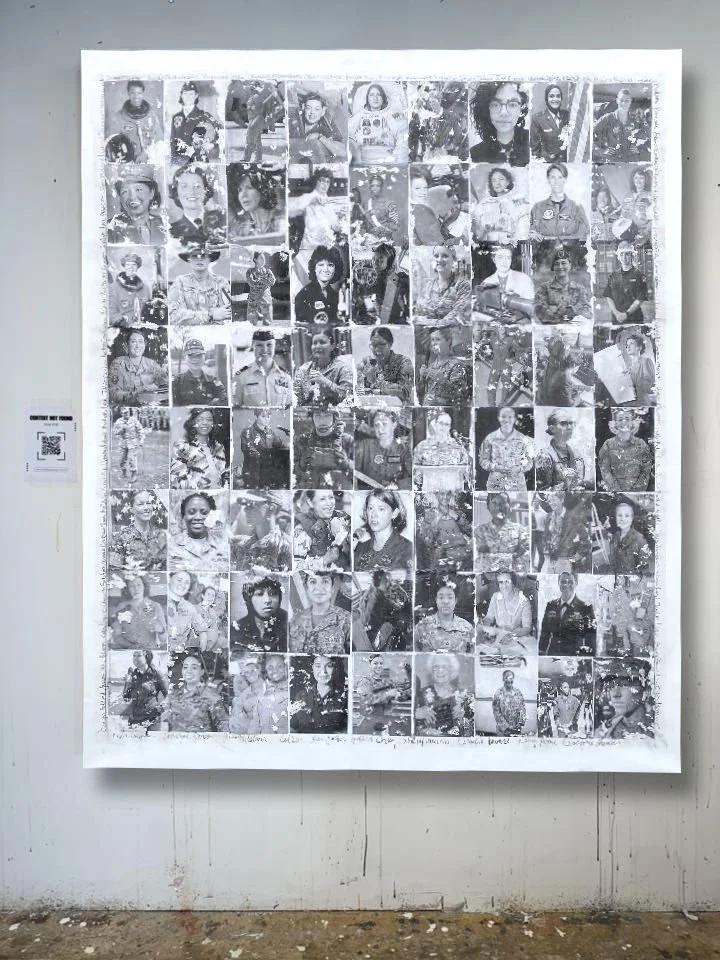

Once I had gathered and documented the images, each one saved along with any available names, ranks, or identifying information, I began the building the painting itself.

I first decided on the overall scale of the piece and the size each portrait would need to be in order to hold presence but also work within the larger composition. Each image was opened in Photoshop and carefully prepared. I converted them to grayscale, reversed them for transfer, and layered in a transparent white background to ensure a uniform contrast across all portraits. Every detail mattered. I laid out the images two per page on 8.5 x 11 paper and saved each batch in groups of around twenty.

With the images printed and trimmed, I turned to the canvas. I mapped the surface, measured spacing, and marked where each image would lie. But instead of assigning them intentionally, I shuffled the 72 portraits face down. I wanted the final layout to reflect the randomness of erasure - that none of these women had chosen to be deleted. I drew each one at random, turned it over, and paused. I thought about the woman I was placing. What she gave. Who she might have been. I did this seventy-two times.

The transfer process itself was physical and intimate. I applied gel medium to the canvas and pressed each image down with my hands, making sure it adhered fully to the surface. I waited 24 hours, then began the delicate work of removing the paper. One by one, I soaked each section with warm water and used my fingertips to roll the paper fibers away, slowly revealing the image beneath. It was slow. Messy. And deeply human.

Once all images were revealed, I added additional media to the surface and sealed the entire painting. Around the edges of the canvas, I wrote the names of each woman I could identify.

At first, this project came from a place of anger. I was outraged that these women, and what they represented, were being erased without acknowledgment. But as I worked, the project began to shift. I realized that like everything I create, this too needed to carry light. It needed to elevate, honor, and witness - not just resist.

And that’s what Content Not Found became. A protest, yes. But also a preservation. A tribute.